Theory - Beyond Busy: Why Teachers Should Monitor Both Behavioral and Cognitive Engagement

Oct 16, 2025

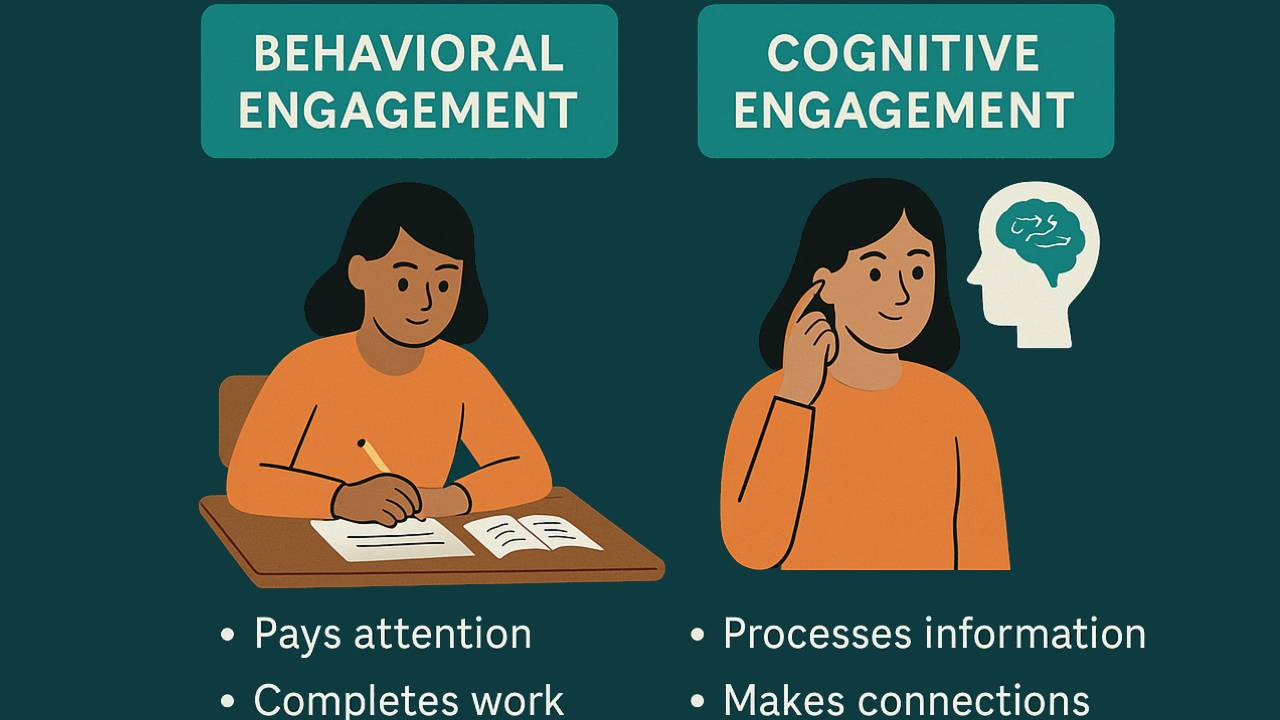

Teachers often equate a quiet, compliant, and industrious classroom with learning. Students appear attentive, complete their work, and respond when called on. These contribute to a well-managed classroom and are indicators of what cognitive scientists refer to as behavioral engagement. Yet those same scientists remind us that being busy is not the same as learning. True learning requires cognitive engagement, the mental effort students invest in processing, connecting, and making sense of new information.

From Attention to Thinking

Cognitive engagement represents the point where thinking becomes learning. Daniel Willingham (2009) succinctly captured this relationship, saying, “Memory is the residue of thought.” Students remember what they think about, not what they merely do. A learner can copy notes or complete a worksheet with full behavioral compliance yet devote minimal thought to developing meaning and ability. Learning, therefore, is not the product of activity itself but of the mental processing that accompanies that task.

This principle is echoed across decades of research. Craik and Lockhart’s (1972) Levels of Processing theory showed that information processed deeply for meaning leads to better retention than information processed shallowly through rote rehearsal. Similarly, Kirschner, Sweller, and Clark (2006) argue that meaningful learning occurs when instruction effectively manages cognitive load, ensuring that working memory resources are devoted to processing, organizing, and integrating new information. When students are behaviorally active in tasks that demand significant mental effort, such as following complex procedures or managing multiple steps, their working memory can become overloaded. According to Cognitive Load Theory (Sweller, 1988; Kirschner, Sweller, & Clark, 2006), this occurs when the extraneous load of performing the task consumes limited cognitive resources. When that happens, students have little capacity left for the essential work of organizing and integrating new knowledge, resulting in less meaningful or enduring learning.

What Teachers Can (and Can’t) See

The challenge is that behavioral engagement is easy to observe, as evidenced by on-task behavior, responsiveness, note-taking, and participation. Cognitive engagement, on the other hand, is invisible unless students externalize their thinking. Teachers can utilize the Cognitive Engagement Observation Checklist to begin building the habit of monitoring their learners for signs of cognitive engagement, including verbalizing reasoning, generating questions, connecting to prior knowledge, and using metacognitive language (“I realized that…” or “I changed my thinking because…”). A teacher needs to make a learner’s thinking visible so they can provide proper feedback on how to improve their understanding of the concept or the ability to execute the strategy without significant errors or omissions.

When teachers look for these “artifacts of thought,” they are observing the mental work that drives durable learning. As Sweller’s Cognitive Load Theory suggests, effective instruction should guide students to focus their limited working memory capacity on meaningful processing rather than surface activity (Sweller, 1988).

Why Monitoring Cognitive Engagement Matters

Focusing only on behavioral engagement risks reinforcing compliance over cognition. Students may appear successful while relying on recognition or procedural completion. Chi and Wylie (2014) classify this level of engagement as active engagement, which is above passive, on their ICAP Framework, but below the deeper constructive and interactive levels that most powerfully support learning. Monitoring both behavioral and cognitive engagement allows teachers to:

- Differentiate participation from processing

- recognizing when students are performing tasks versus constructing understanding.

- Adjust instructional design

- introducing prompts or tasks that elicit reasoning, explanation, and reflection.

- Gather evidence of learning

- using student talk, written work, and metacognitive reflection as data points.

The Teacher as Cognitive Architect

Kirschner and Sweller often describe teachers as architects of cognition: professionals who design learning environments that reduce unnecessary load and increase opportunities for deep processing. By intentionally monitoring cognitive engagement, teachers can evaluate whether their instructional design effectively prompts students to think about the concepts and skills represented in their proficiency scales, leading to long-term retention and transfer of those concepts and skills.

In Summary

Learning is not guaranteed by engagement alone. As Willingham (2009) reminds us, students learn what they think about. Behavioral engagement may create the conditions for attention, but cognitive engagement transforms attention into understanding. The task for teachers is not merely to keep students busy, but to keep them thinking because it is in the thinking that learning truly occurs.

If you are interested in discussing cognitive engagement and other cognitive theories, join the Learning Hub and post in the Community Channels, register to attend an office hour, or send a direct message to the Learning Hub Faculty.

Next week's Friday Blog will focus on "use-it-tomorrow" strategies you can bring directly to your classroom to support monitoring for cognitive engagement.

References

Chi, M. T. H., & Wylie, R. (2014). The ICAP framework: Linking cognitive engagement to active learning outcomes. Educational Psychologist, 49(4), 219–243.

Craik, F. I. M., & Lockhart, R. S. (1972). Levels of processing: A framework for memory research. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 11(6), 671–684.

Kirschner, P. A., Sweller, J., & Clark, R. E. (2006). Why minimal guidance during instruction does not work: An analysis of the failure of constructivist, discovery, problem-based, experiential, and inquiry-based teaching. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 75–86.

Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cognitive Science, 12(2), 257–285.

Willingham, D. T. (2009). Why don’t students like school? A cognitive scientist answers questions about how the mind works and what it means for the classroom. Jossey-Bass.